1. Dialectics for dummies?

Subtlety is lost with me. I start with vulgar understandings, then the wave crests, nearing something mature and considered, and recedes back to where I started. Of course, this could be read in the reverse, from crest to crest, valuing moments of enlightenment broken by whatever its opposite is. But I am obsessed with beginnings, and the crest will always be to me when where I started begins to pull me back.

That said, I have a very vulgar idea of how dialectical thinking works: It means holding contradictory views simultaneously on a single issue. I say “holding” but I think it’s more about how those views are expressed, given, conversed. If my friend particularly likes gardening, I’m the sort of person who will ask questions about it, listen to what they have to say about it, even though I don’t like gardening. Then if I talk with my other friend who doesn’t like gardening, who thinks it’s middle-class and nostalgic, I’ll probably agree with them on some points, even if not completely. Both of these views of gardening are contingent with one another. They are more or less predictable positions on what is otherwise the material reality of gardening, its practice and economy. That’s to say they are ideas about something actually occurring; gardening—everyone doing it, the businesses marketing their products about it, the home-grown food being eaten from it, the passing conversations and thoughts that people have while doing it—is happening. Ideas are more than brief impressions, to be sure, but they are far less substantive than chemical reactions. I could, based on my opinion of gardening, change how it happens, but even that would mean my idea becomes action, which is something else.

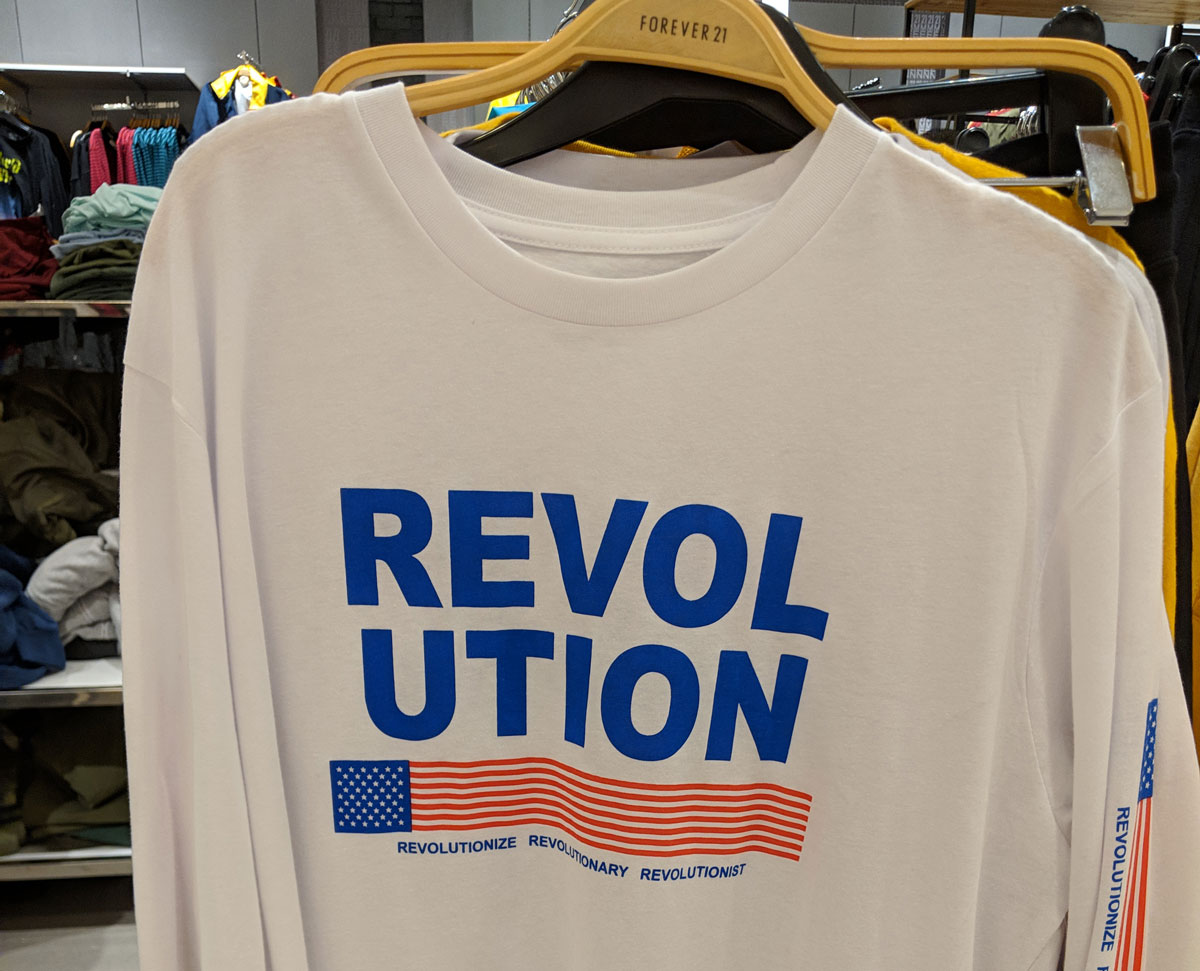

I understand most debates in this way and I believe this is more or less the essence of dialectical thinking. My obsession with beginnings means I can’t take an idea or concept as just what it is. Revolution during the French Revolution, forged under the oppression of the Bourbon regime, doesn’t mean that same thing that it does when it’s used in a Forever 21 store. Reality is fundamentally arbitrary, changing, historical. Revolution can’t be more than what we call it and how we describe and use it. And, whether the word exists or not (to avoid confusion with post-structuralism), the conditions that give meaning to revolution—whether it’s a new product or a new social order—anticipate its use. We might not know revolution until we see it, but we know that it has been meaningfully to people in the past.

Ultimately, I take a position. But I do it with an understanding of a wider frame, of the contradictions that create the possibility for discussion and conflict. This helps me to communicate what I think and, maybe unintentionally, to find humanity in my opponent.

2. Be more mindful (of how self-awareness moralism works).

The mindfulness movement is the moral order of the bourgeoisie. It’s how more productive employees work. It sanctions a moral superiority because it implies in every instance that if only the world were more mindful, things would be so much better. This, of course, means that if only those unmindful people got mindful or disappeared, We the Mindful would have the peace and quiet we deserve.

Mindfulness ignores the complexity of the world and life, seeking to put the blame on bad players, bad guys, or whoever fits the bill. It assumes being mindful has an inherent goodness about it, that people are kinder and more thoughtful to one another when they are more mindful. This is an inherited belief from Buddhism, where mindfulness practice was (and generally is) a monastic practice to help monks orient themselves to the dharma. But are nasty people always distracted and uncalculated? A Buddhist might suggest that they are lost in an illusion of self out of which their attachment is based (dukkha), which in turn drives their greedy, selfish behavior. Once they became aware that their self doesn’t actually exist, the framework of their evil would dissipate.

Self-awareness, which is the general imperative of mindfulness, exposes us to a barrage of marketing: therapeutic services, lifestyle tips, guides, stories of personal transformation, clichés to hang (or post) on our walls, and exercise regimes. The more we are told to be more aware and mindful, the more we discover our need for help. We realize we can’t make it alone, which makes us more receptive to advertising and other didactic content that seeks to train us, prepare us for a certain way of living that, we trust, is better than our current behavior.